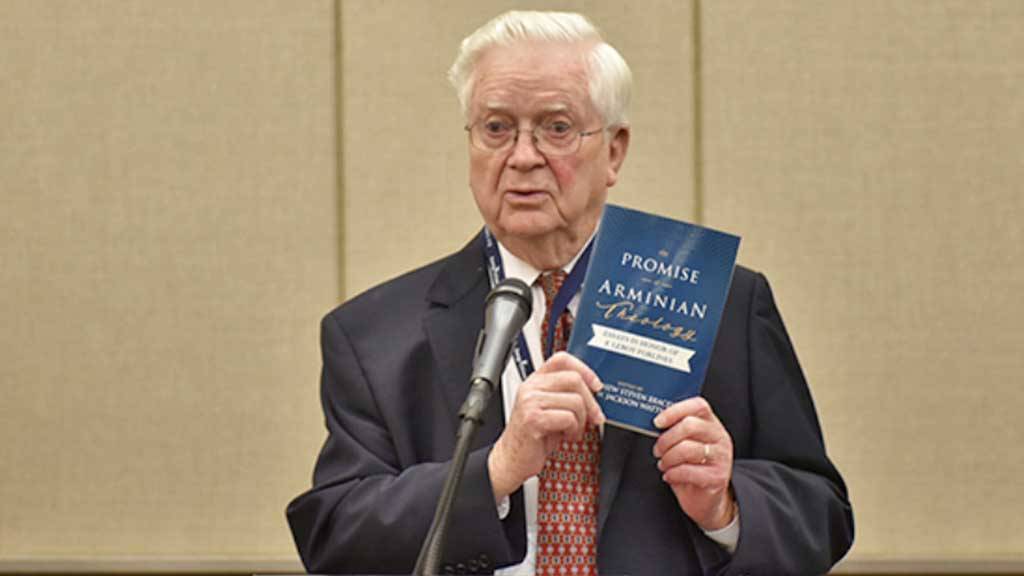

In describing the profound impact of F. Leroy Forlines on students, pastors, and laypeople, one writer said that “his most valuable contribution was a theology that is big enough, deep enough, and meaningful enough to impact all of life.”[1] One way in which Forlines has had a big, deep, and meaningful impact in my own life is the area of the arts, specifically how the Christian should pursue and interact with the arts.

By his own testimony, Forlines enjoyed visiting art museums with his wife. The thought of this respected theologian moseying around an art gallery in the middle of Russia is fascinating. But for Forlines, the arts are more than a hobby. As one reads his beloved book, The Quest for Truth: Theology for a Postmodern World, it becomes evident that the arts are interwoven with his approach to theology, life and culture.

Within Quest, Forlines makes several references to the arts. While his primary goal is not to prove the value of the arts, his references make a case for his approach to the arts as foundational to the human—and especially the Christian—experience. Unfortunately, Forlines refers to only two art mediums: music and painting. I will evaluate Forlines’s view on these two art forms in light of a vital theological foundation, the Cultural Mandate.

Forlines on the Cultural Mandate

Before evaluating his references to the arts, we must come to understand and appreciate a vital theological foundation upon which Forlines builds his approach to the arts. At the close of his discussion on sanctification, he argues that “Sanctification is to extend to all of life’s experiences.”[2] He goes on to say,

In determining the scope of sanctification, we need to go back to the meaning of being created in the image of God. We were designed to be in the functional likeness of God. This should be seen in the entire scope of human experience. All our experiences in every area of life are to be affected by the divine likeness that we are to manifest. The design of sanctification is to restore the functional likeness of God that was lost in the fall. We were designed to be in the moral likeness of God. When we speak of the moral likeness of God in this context, we are using the word moral in its broadest meaning. We are to be holy, loving, and wise because God is holy, loving, and wise. We are to be concerned about ideals, beauty, and excellence because God is the quintessence of the high and the lofty. This likeness of God is to be highly evident as we carry out the divine mandate to exercise dominion over the earth and its inhabitants, and as we obey the Great Commission.[3]

F. Leroy Forlines, The Quest for Truth

Because “we dare not forget that God is a God of beauty, majesty, and excellence,” and since “every human being has a potential, and that potential should be developed to its fullest and highest level of achievement,”[4] Forlines issues as plea for a revival of Christian Humanism. He acknowledges that the humanities are generally viewed as architecture, art, music, and literature, but his “aim in calling for a revival of Christian Humanism is to include these areas, but also to extend the concern for beauty, excellence, and order to every area of life.”[5]

Forlines roots his philosophy in the Genesis narrative, when God commands mankind to exercise dominion over the creation. This is called the Cultural Mandate. “In carrying out this mandate, we are to aspire to the high ideals that are set for us by our responsibility to be in the likeness of God. We are to aspire to bring the entire scope of life under the Lordship of Christ.”[6] This is all in keeping with Scripture’s declaration that the world has been placed in subjection under Christ. Even though “at present, we do not yet see everything in subjection to him,” nothing is outside of the control of Christ (Hebrews 2:7-8). Abraham Kuyper has pertinently noted, “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry, Mine!”[7]

It is a tendency among Christian thinkers to unnecessarily label certain aspects of this world as worldly. Forlines acknowledges that while “fallen man cannot bring all of life into conformity to the likeness of God,” the “image of God is not completely silent in fallen human beings.”[8] Many achievements have been attained within the arts and sciences by non-Christians; believers should “study these achievements and critique them in the light of the revealed truth in the Bible.”

A White Canvas as a Sign of Decline

As already mentioned, Forlines expresses his appreciation for painting by recounting his time in Russia with his wife Fay in 1996. “We had toured many art museums throughout Russia and marveled at the paintings of many master painters, including Rembrandt.”[9] It is no surprise that Forlines mentions that he admires the beauty and excellence of the art of Rembrandt (1606-1669), the Dutch painter and etcher whose details and intricate biblical scenes define the Dutch Golden Age. (I can think of at least one other Dutchman that Forlines agrees with.)

Forlines’ discussion on painting is for the purpose of demonstrating the presence of postmodernism in the culture. Postmodernism is a “relativistic system of observation and thought that denies absolutes and objectivity.”[10] For the postmodernist “everything is true in the sense of ‘true for you’ and ‘true for me.’ Nothing is true in the sense of true by a standard of absolute Truth.”[11]

As an illustration of postmodernism, Forlines goes on to critique other art present at the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. “We saw a display of art from Great Britain produced in the 1990s. One of these works was simply a canvas painted white . . . Compared to the great classical works of art, these recent British works were pitiful.”[12] Forlines accurately describes the rapid decline of painting over recent years, specifically how it mirrors modernity’s view of the truth. A 2014 report states that an untitled 1961 work by American conceptualist Robert Ryman sold at a New York Auction for $15 million.[13] (Other than texture in the paint, Ryman’s piece was little more than white paint on a white canvas.[14])

The response from Forlines is full of grace, seasoned with salt: “Instead of ridicule for these artists and their works, we should have compassion . . . We cannot simply condemn this kind of art out of existence . . . We must learn to address the despair and hunger in people’s hearts with the Truth that sets people free.”[15] This gospel-centered tone is the usual response from Forlines at the intersections of the arts, theology, the gospel, and culture.

No Room for Artistic Snobbery

Throughout his book, Forlines calls for beauty and excellence but never does he call for artistic snobbery. Subduing the earth and having dominion acknowledges a process; it is not a call for immediate perfection. When children create refrigerator art, their parents do not sneer at the artwork. Rather, they treasure and admire it in all of its simplicity. In a similar way, when we hear reports of African Christians coming together to build a place of worship in the fashion of their straw-roofed mud huts, we as Westerners still see beauty, even though it does not match our forms of architectural art.

When Forlines labels the white canvas “pitiful,” this is not the same as refrigerator art and mud huts. He is recognizing a deliberate dumbing-down which is a sign of postmodernism. I believe Forlines would agree. In the midst of his call for beauty and excellence in a section entitled The Need for Balance, he states, “The complication presented by sin, the shortage of time, money, ability, help, etc., limit what we can do. We cannot do everything that we would like to do. Frequently, we need to look at a situation from several different angles . . . the best is not always possible.”[16]

The Music of the General Culture

This statement conveys Forlines’s view on the music of the general culture:

“Nothing reflects the spirit of the age as much as people’s attitude about the areas covered by ideals, beauty, and excellence. It is reflected particularly in the way people dress and the kind of music they listen to.”[17]

F. Leroy Forlines, The Quest for Truth

This statement has a nuance that may be misunderstood if not read carefully. Notice that Forlines specifies the music that people listen to, as if to suggest a difference between the music that is created by artists and the music that is enjoyed by the general culture. This is important because Forlines’s main reason for bringing up music, specifically the music which is listened to, is a sign of postmodernism which has crept into the general culture. Other than one passing statement, he does not mention higher forms of music (e.g., classical music, arts music) as he did with painting.

Forlines quotes one of his sons who speaks of his upbringing:

“I wish I had a dollar for every museum, historical landmark, and exhibit that we saw. Our exposure to music, good music, was very broad. I learned to love the arts, flowers, and beauty in general because of the continual influence of my mom.”

F. Leroy Forlines, The Quest for Truth

As we continue to evaluate Forlines’s references to the music of the general culture, it is interesting to note that he groups together “the way people dress” and “the music they listen to.” He does so in the quote at the beginning of this section and then three more times: the “rejection in our culture of the traditional concern for ideals is a manifestation of the spirit of the age. This rejection is seen in matters like music and dress [emphasis added].”[18] He groups these two things again: “The areas that have been hit the hardest on the grassroots level are music and personal appearance [emphasis added].”[19] And again: “They suffer internally over the deterioration of music, dress, and civility [emphasis added].”[20] The mention of “civility” (formal politeness and courtesy in behavior or speech[21]) indicates all the more that he is thinking in terms of general culture.

This lumping together of dress and music is a suggestion that the expression of the culture through appearance and art enjoyment should be taken seriously. This thinking on the part of Forlines is in keeping with Francis Schaeffer’s “line of despair” given in Escape from Reason, a work with which Forlines is familiar (he cites it in Quest). Schaeffer suggests that the line of despair starts “first in philosophy, then art, then music, then general culture, which could be divided into a number of areas. Theology comes last.”[22]

So, why does Forlines make an issue of the music of the general culture? He emphatically states that believers “underestimate the damage that postmodernism has done to the cause of Christ when it undermines ideals.” [23] We have a tendency to take a boys will be boys approach to these matters. We rationalize that these habits of the general culture are not that big of a deal. Forlines pushes up against this mindset when he says, “It is not as easy as saying these things do not matter. This negative attitude crosses over into the non-negotiable moral areas.” [24]

Music in Worship

Forlines recognizes that the music practiced and enjoyed within the general culture will have an effect on church worship:

It is thought that the key to reaching today’s people is to make changes in the style of music and a few other things in the way that the service is conducted before the pastor brings the message. Regardless of what value there may or may not be in these suggestions, I think that the matter of reaching people who have been conditioned by postmodernism is much deeper than that. It is a tragic underestimation of what is involved in rescuing those who are held captive to postmodernism or the modernism mood to think that the major factor involved in reaching these people is a change in worship style.[25]

F. Leroy Forlines, The Quest for Truth

Lest he be misunderstood and viewed as overly rigid, Forlines concedes that we will not all “agree on matters of form.” His call is that we come to an “agreement on substance.”[26] In other words, he is not calling for conformity to one style of music (or one style of dress); he is not suggesting that we only listen to and worship with classical music.

What we must agree on is that the style of music we choose for worship should not distract or take away from doctrine and truth and should be an example of beauty and excellence. “Both the long-list legalists and the short-list legalists have failed to give proper emphasis to substance . . . To give proper emphasis to substance will not erase all differences about form, but it will make it easier to discuss the question of appropriate form.”[27] A focus on substance with a conviction that Scripture is God’s authoritative and absolute Truth is in direct opposition to postmodernism’s suggestion that truth is anything one wants it to be.

The Church must evaluate which practices of the general culture it adopts, because these practices will eventually impact the Church’s theology. Even still, the reverse is true—the practices we adopt are a direct reflection of our understanding of theology. There is a clear link between practice and substance.

Conclusion

Paul challenges his readers to “approve what is excellent” (Philippians 1:10) and goes on to tell the Philippian believers to seek out and think on things that are true, honorable, just, pure, lovely, and commendable (Philippians 4:8).

Leroy Forlines is a practical theologian, an in the trenches kind of thinker. In the midst of his discussion on beauty, excellence, and majesty, he shows grave concern for the ones created in God’s image who remain entrapped by sin. He warns believers:

“If your church does not have people who were saved out of deep sin, it is not because you are doing a good job, it is because you are not ministering to today’s world.”[28]

F. Leroy Forlines, The Quest for Truth

The approach to life that Leroy Forlines advocates is not just for the middle- to upper-class professional man, who began playing cello at the age of eight, attended a state university, and is chairman of the deacon board at the local Baptist church. Beauty, excellence, and order can be attained by the drug-addicted single mother who dropped out of high school and has never darkened the door of a church, because she is made in the image of her Creator.

“If sin had not entered the picture, there would be no problem in living the whole scope of our lives in complete conformity to God’s likeness. Sin changed things.”[29]

F. Leroy Forlines, The Quest for Truth

Ultimately, that’s what Redemption and Sanctification are all about—seeing beauty, excellence and order restored, as God originally intended.

[1] Jackson Watts, “F. Leroy Forlines: Theology for All of Life,” Helwys Society Forum, entry posted February 25, 2013, http://www.helwyssocietyforum.com/?p=3359 (accessed August 16, 2016).

[2] F. Leroy Forlines, The Quest for Truth: Answering Life’s Inescapable Questions (Nashville: Randall House Publications, 2001), 229.

[3] Ibid., 230.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 232.

[6] Ibid..

[7] Abraham Kuyper, inaugural lecture at the Free University of Amsterdam, October 20, 1880, quoted in Abraham Kuyper: A Centennial Reader, ed. James D Bratt (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1998), 488.

[8] Quest, 232

[9] Ibd., 411.

[10] “Postmodernism,” Theopedia, accessed October 10, 2016, http://www.theopedia.com/postmodernism.

[11] Forlines, Quest, 16.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Leonid Bershidsky, “Why Pay $15 Million for a White Canvas?” Bloomberg, November 14, 2014, accessed August 17, 2016, https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2014-11-14/why-pay-15-million-for-a-white-canvas.

[14] Ryman’s work can be viewed here: http://tinyurl.com/Ryman-untitled-1961

[15] Forlines, Quest, 411-412.

[16] Ibid., 234.

[17] Ibid., 231.

[18] Ibid., 248.

[19] Ibid., 460.

[20] Ibid., 428.

[21] “Civility,” Oxford Dictionaries, accessed August 25, 2016, http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/ definition/american_english/civility.

[22] Francis A. Schaeffer, Escape from Reason: a Penetrating Analysis of Trends in Modern Thought (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books, 2007), 58.

[23] Forlines, Quest, 248.

[24] Ibid., 248.

[25] Ibid., 428.

[26] Ibid., 248.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid., 248.

[29] Ibid., 232.