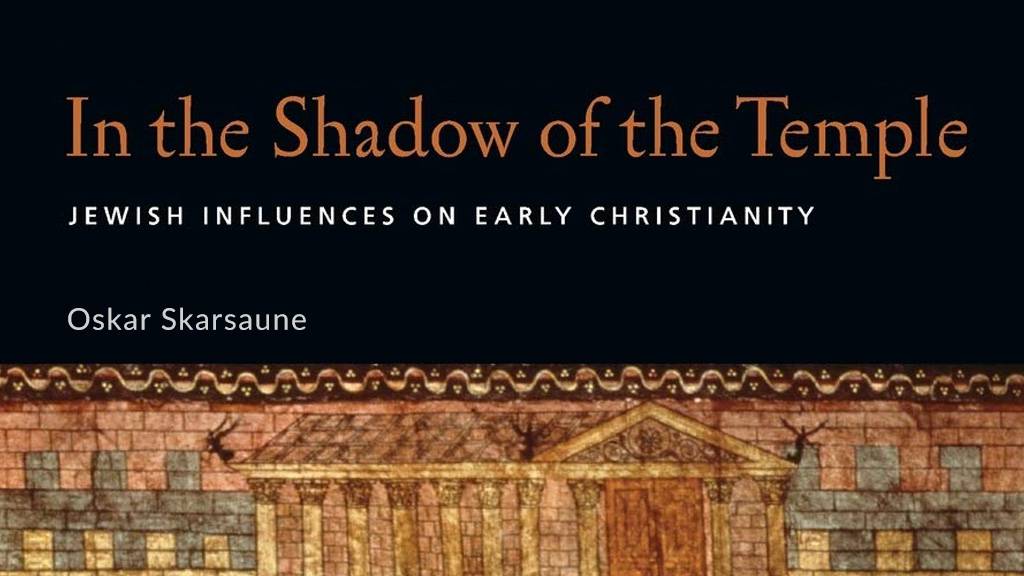

Students of Scripture have long recognized the Jewish influence on the Christian church during the time of Christ and the Apostles. Even after the destruction of the Jerusalem temple in AD 70, one might expect some residual effects to linger on into the second century. But Oskar Skarsaune, professor of church history at Norwegian Lutheran School of Theology in Oslo, Norway, identifies Jewish influences on Christianity even into the fifth century, 400 years after the destruction of the temple. Additionally, Skarsaune does not only recognize the Jewish influence during the period of the New Testament, he also traces significant events occurring in the intertestamental period, 200 years before the resurrection and ascension of Christ. By observing the events during the time of the Maccabees, the church during the time of the apostles, the Ante-Nicene church, and even the church under Constantine’s rule, this book demonstrates that the Christianity is influenced by and indebted to the Jewish faith in ways not usually recognized by Christians today. Although overall in chronological order, this volume is not composed as a strict narrative (13), but is rather arranged thematically with supporting “episodes, snapshots, and anecdotes” (13). A helpful “Temple Square” section in most chapters draws out vital themes and provides additional reading. Throughout his work, Skarsaune provides his own commentary and interpretation of the events he draws out.

The author divides the book into four sections. The first section deals with Hellenism (the cultural dimension), the Roman Empire (the political dimension), Israel across the Diaspora (the geographical dimension), and Israel in Jerusalem during 200-year period before the birth of the church (23–134). Perhaps the most helpful chapter is “How Many ‘Judaisms’?” (103–128). In it, the author presents a history of the changes in the various parties of Judaism covering mainly the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, priests, rabbis, lay Jews, the Qumran community, and zealots. The most important factor that influenced these groups was their proximity to the temple; those who lived in various parts of the Diaspora would have been dependent on the synagogue community which appears in the historical record as early as 250 BC (123). Skarsaune helpfully explains that the synagogue is a layman’s institution that focused primarily on the expounding of Scripture and prayer (124).

The second section covers many of the same topics as the first but continues to trace the progression of these topics during the first two centuries. New subjects in this section includes the mission to the Gentiles, the encounter with paganism, the challenge of heresies, and second-century anti-Jewish sentiments (135–278). At the beginning of this section, the author explains Jesus Christ’s place in Judaism—as much as many Christians would not like to accept—was among the Pharisees (139). The author also provides a helpful explanation (and among the best in print) of the anti-Jewish debate that comes about in the second century (259–276). This sentiment can be seen mainly in the Letter of Barnabas, Dialogue with Trypho (Justin), Against the Jews (Tertullian), and fragments from later church fathers that recount a debate between Jason and Papiscus. Especially amidst controversy, we witness the continued influence of Judaism on Christianity.

Skarsaune’s third section focuses on the sustained Jewish influence as the Church develops major matters of faith and order in the ante-Nicaean period (279–424). Such matters include canon, Christology, the roll of the Spirit, conversion and baptism, worship, and the Eucharist. For worship students, the chapter entitled “Worship and Calendar: The Christian Week and Year” is immensely useful (377–378). “Many scholars believe that from the beginning, the Gospels we read in Christian worship very much like the Torah in Jewish; that is, the Gospels were read in continuous order, the reader taking up next Sunday where they left off the Sunday before. . . . To this Gospel reading an appropriate haftarah (or selection) from the Prophets would then be added” (385). The author also lays out the Christian year, as practiced in the early church, and makes parallels to Jewish practice, highlighting Easter and Pentecost.

The fourth section is an epilogue (425–446). The purpose of the final chapter is not to tie up loose ends or summarize previous material; the author provides new content that focuses on the Constantinian revolution. During this time, Constantine initiated a deliberate breaking away from the Jews. (Again, the Jewish influence is still strong, so much that a break is required.) But we should not understand that this occurred among laypeople immediately. We do find a “surprisingly high degree of mutual socializing and a mutual attitude of sympathy and friendliness among parts of the grassroots constituency in both communities” (442).

Oskar Skarsaune is a perceptive historian and a fascinating author. His writing style is both artistically delightful and historically profound. I do not identify significant weaknesses in this work, but the reader should understand that the author does not hesitate to give his own insights and commentary. In the Shadow of the Temple: Jewish Influences on Early Christianity is an important contribution for helping today’s church better understand the context of the Scriptures and a major influence on our brothers and sisters of early centuries. I wholeheartedly recommended this book for scholars, ministry leaders, and laypeople.

For more book reviews, see the Worship Research category of A Thing Worth Doing.

One Response

We love to receive your teachings

We are from Horeb biblical Hebrew school India